|

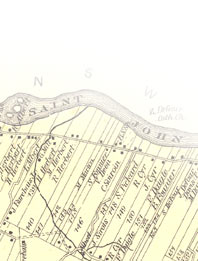

The Catholic Church has had a dominant presence in the Upper St. John

Valley ever since the arrival of the first French settlers in 1785. During

the initial years of settlement, the parish priest at L'Isle-Verte, Québec,

ministered to both the French and the Maliseets of the Madawaska territory,

making sporadic journeys over the long portage road that linked the St.

John and St. Lawrence rivers. According to oral tradition, the settlers

erected a primitive chapel in 1787. The exact site of the chapel is unknown,

though the inhabitants of both present-day St. David in Madawaska, Maine,

and Saint-Basile, New Brunswick, have claimed it to have been within their

respective parishes (Albert [1920] 1985: 45-46).

The Catholic Church has had a dominant presence in the Upper St. John

Valley ever since the arrival of the first French settlers in 1785. During

the initial years of settlement, the parish priest at L'Isle-Verte, Québec,

ministered to both the French and the Maliseets of the Madawaska territory,

making sporadic journeys over the long portage road that linked the St.

John and St. Lawrence rivers. According to oral tradition, the settlers

erected a primitive chapel in 1787. The exact site of the chapel is unknown,

though the inhabitants of both present-day St. David in Madawaska, Maine,

and Saint-Basile, New Brunswick, have claimed it to have been within their

respective parishes (Albert [1920] 1985: 45-46).

In 1792, only seven years after the arrival of the first settlers, the

territory of Madawaska was established as a parish by the bishop of Québec.

The new parish, named Saint-Basile, was only the third to be erected in

post-deportation Acadia. Despite its early presence in the area, the Church

had great difficulties in establishing its authority over the settlers.

The first resident parish priest, François Ciquart, complained to his

bishop in 1794 that he was disappointed with the residents, whom he had

expected to be more devoted to the Church (Desjardins 1992: 55). During

the following years, cooperation between the local population and the

Church improved somewhat. The major problem commented on by the priests

was that of the long distances that parishioners living in outlying areas

had to travel to attend mass.

In 1827, two mission chapels were erected. One, in present-day Frenchville,

Maine, was named Sainte-Luce, while the other, named Saint-Bruno, was

situated in a community that encompassed present-day Saint-Léonard, New

Brunswick, and Van Buren, Maine (known as Grande-Riviére). St. Bruno became

a full-fledged parish in 1838, and St. Luce followed five years later.

From then on, several new parishes were formed as the population of the

Valley increased, and churches were built all along the Upper St. John

River.

In 1827, two mission chapels were erected. One, in present-day Frenchville,

Maine, was named Sainte-Luce, while the other, named Saint-Bruno, was

situated in a community that encompassed present-day Saint-Léonard, New

Brunswick, and Van Buren, Maine (known as Grande-Riviére). St. Bruno became

a full-fledged parish in 1838, and St. Luce followed five years later.

From then on, several new parishes were formed as the population of the

Valley increased, and churches were built all along the Upper St. John

River.

Recognizing the disputed claims to the Upper St. John Valley by both

the United States and British North America, the Catholic bishops of Boston

and Québec took action in 1811 to avoid disputes over Church authority

in the region. Bishop Cheverus and Bishop Plessis agreed to name each

other as Vicar-General; thus, each was bound to honor the actions of the

other in the disputed territory (Dubay 1979: 6; Guilday 1922: 620-24).

|

|

|

Although the Maritime Provinces formed a distinct diocese from 1829 onward,

priests continued to be sent from Québec to the Upper St. John Valley

until 1857 because of a  shortage

of French-speaking priests in the Maritimes (Desjardins 1992: 50). From

1860 onward, the Valley was part of the new diocese of Chatham, which

included all of northern New Brunswick. Though the American-Canadian boundary

split the Valley in 1842, residents of Maine continued to be under the

jurisdiction of the Church in Québec and New Brunswick until 1870, when

their parishes became officially affiliated with the diocese of Portland,

Maine. shortage

of French-speaking priests in the Maritimes (Desjardins 1992: 50). From

1860 onward, the Valley was part of the new diocese of Chatham, which

included all of northern New Brunswick. Though the American-Canadian boundary

split the Valley in 1842, residents of Maine continued to be under the

jurisdiction of the Church in Québec and New Brunswick until 1870, when

their parishes became officially affiliated with the diocese of Portland,

Maine.

Religion has played a central role in local society ever since the Church

became firmly established in the mid-19th century. As was the case in

French Catholic communities elsewhere in North America, local priests

were community leaders, and most schools were run by members of religious

congregations. However, the following story, related during data collection

for this report (focus group 1993), hints at the tension that still exists

between ingrained values of staunch independence and respect for local

clerical authority:

That's like the story of the old man sitting in the front pew of

the church, and the priest was really preaching fire and brimstone.

And he said, "You people in this parish are all going to hell if you

continue behaving the way you do." [The old man] thought it was funny.

He laughed, you know. So the priest saw that, and the priest repeated

himself again. And the old man laughed a little louder, and so [the

priest] took him to task. He says, "Sir, why is it 'cause I make that

statement you find it funny?" [The old man] says, "Because I'm not from

this parish."

Public and private images and expressions of religion abound in the Valley.

The strength of Catholicism is clearly demonstrated throughout the Valley

by the many beautiful churches and associated buildings, statuary, wayside

crosses, and shrines. Yet there are two very different aspects to religious

practices of French-speaking Catholics, the official and the unofficial.

Both are manifested in the religious life in the Valley. Daily devotions

such as the recitation of the rosary, novenas, attendance at mass, and

Sunday vespers are shared to varying degrees by members of the community

(Dubay 1983: 78). These are official rites of the Church, as are the rituals

associated with holidays such as Christmas, Easter, and All Saints Day.

Public and private images and expressions of religion abound in the Valley.

The strength of Catholicism is clearly demonstrated throughout the Valley

by the many beautiful churches and associated buildings, statuary, wayside

crosses, and shrines. Yet there are two very different aspects to religious

practices of French-speaking Catholics, the official and the unofficial.

Both are manifested in the religious life in the Valley. Daily devotions

such as the recitation of the rosary, novenas, attendance at mass, and

Sunday vespers are shared to varying degrees by members of the community

(Dubay 1983: 78). These are official rites of the Church, as are the rituals

associated with holidays such as Christmas, Easter, and All Saints Day.

Non-official practices are often related to Church rites, but they involve

traditional beliefs in addition to sacred elements. The blessing and distribution

of holy water, for example, has long been an important function of local

parish priests. But the actual use of this holy water is often established

by tradition and custom.

Due to its sanctity and because many believe in its power to protect

the home, holy water is kept and often prominently displayed in local

homes. Don Cyr of Lille in Grand Isle, Maine, shared an insight concerning

the importance of holy water to his family. According to Cyr, his grandfather,

Fred Albert from Saint-Hilaire, New Brunswick, would say that "when there

was a bad storm and thunder, it would be raining harder inside than outside."

The elder Albert was referring to the quantities of holy water sprinkled

throughout the house to protect it from the ravages of a storm.

Cyr and others also tell about l'eau de Páques (Easter Water).

Just before sunrise on Easter Sunday, local residents collect water from

a spring. Some bring it to a priest to be blessed, while other people

believe that l'eau de Páques is sacred because it is gathered on

Easter Sunday morning, and don't consider it necessary to have it blessed

by a priest. L'eau de Páques is considered a powerful holy water

that will never go stale or lose its purity (Brassieur 1992). The Upper

St. John Valley is one of the few areas where the custom of gathering

l'eau de Páques has been maintained to the present day, while it

used to be common all over French Canada and Acadia (Labelle 1977).

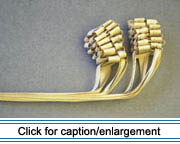

One type of religious object prominently displayed in houses and barns

throughout the Valley are blessed palm leaves (les rameaux).The palms are distributed

to parishioners annually on Palm Sunday. Sometimes they are braided into

a decorative pyramidal form. Blessed palms are believed to protect a building

from fire caused by lightning. They are used in a similar manner by Cajuns

in Louisiana and French Creoles in Missouri, as well as in all French

areas of Canada.

are blessed palm leaves (les rameaux).The palms are distributed

to parishioners annually on Palm Sunday. Sometimes they are braided into

a decorative pyramidal form. Blessed palms are believed to protect a building

from fire caused by lightning. They are used in a similar manner by Cajuns

in Louisiana and French Creoles in Missouri, as well as in all French

areas of Canada.

|

|