|

The early history of "Acadie" is dominated by 150 years of conflict between

French and British colonial forces, and by interaction with native peoples.

As the colonial battles began to unfold in the 1600s, the Micmacs occupied

present-day Nova Scotia, Prince Edward Island, the Gaspé peninsula of

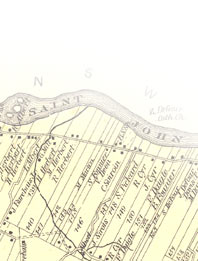

Québec, and eastern New Brunswick. The watershed of the St. John River

was occupied by the Maliseet, while the Passamaquoddy people inhabited

the area around the St. Croix River.

The date of the arrival of the first Europeans in the Micmac homeland

is unknown. Throughout the 16th century, hundreds of small fishing vessels

came to the coast of Newfoundland and to the Gulf of St. Lawrence in search

of cod. They not only fished offshore, but gradually established fishing

stations where they cured their catch (Clark 1968: 75). Consequently,

the northeast coast of North America was well known in the seaports of

France, Spain, the Basque country, Portugal, and West Country England

long before the founding of the colony of Acadia in "New France." French

claim to lands in North America date from three voyages of Jacques Cartier

(1534-1542), particularly the raising of a cross with the royal arms on

the Gaspé peninsula in 1534 (McInnis 1969: 20).

There are two theories regarding the origin of the name "Acadie" or "Acadia."

One attributes it to the explorer Verrazano, who in 1524 named the coastline

of the present-day Middle Atlantic states "Arcadie," in remembrance of

a land of beauty and innocence celebrated in classical Greek poetry. The

name "Arcadie" (with an "r") appears on various 16th-century maps of the

east coast of North America, and has been accepted by many historians

as being the origin of the name "Acadie." The romantic associations of

the term "Arcadie" likely explain why this theory has been widely published

and is even found in recent scholarly works (Daigle 1982). The more plausible

theory is that "Acadie" derives from a Micmac word rendered in French

as "cadie," meaning a piece of land, generally with a favorable connotation

(Clark 1968: 71). The word "-cadie" is found in many present-day place

names such as Tracadie and Shubenacadie in the Canadian Maritimes, and

Passamaquoddy, an English corruption of Passamacadie. Virtually all French

references to Acadia from the time of the first significant contacts with

the Micmacs use the form without the "r", "Acadie." The cartographic use

of "Arcadie" for various parts of the coast of eastern North America may

have prepared the way for the acceptance of "-cadie" from its Micmac source

(Clark 1968: 71).

|

|

|

The King of France began to grant North American fur trade monopolies

in 1588 to finance colonization (Daigle 1982b: 18). Pierre du Gua de Mons

(a.k.a. Sieur de Monts) received a trade monopoly over territory between

the 40th and 60th parallels with the understanding that he establish a

colony. On April 7, 1604, Pierre du Gua sailed from Havre-de-Gráce in

France with 120 men and settled on a small island near the mouth of the

St. Croix River in present-day Maine. They named it Ile Sainte-Croix (holy

cross). In August, Pierre du Gua sent his main fleet back to France and

began preparations for the winter with the remaining 78 members of the

expedition, including the explorer and navigator Samuel Champlain. Nearly

half of the men died of illnesses during the first winter and many more

became dangerously ill. Consequently the colony was moved to a more favorable

site at Port-Royal on the Bay of Fundy, in present-day Nova Scotia. There

the settlers cleared and cultivated land and appeared to be making progress.

However, Pierre du Gua's monopoly was revoked in 1607, the colony was

abandoned, and the settlers returned to France. A new attempt to settle

at Port-Royal was launched in 1610, and a rival colony was established

in 1613 in present-day Maine at St. Sauveur on Mount Desert Island. Later

that year, both settlements were destroyed by British colonists from Virginia.

A map showing the major 17th-century settlements and outposts of Acadia

appears below.

The King of France began to grant North American fur trade monopolies

in 1588 to finance colonization (Daigle 1982b: 18). Pierre du Gua de Mons

(a.k.a. Sieur de Monts) received a trade monopoly over territory between

the 40th and 60th parallels with the understanding that he establish a

colony. On April 7, 1604, Pierre du Gua sailed from Havre-de-Gráce in

France with 120 men and settled on a small island near the mouth of the

St. Croix River in present-day Maine. They named it Ile Sainte-Croix (holy

cross). In August, Pierre du Gua sent his main fleet back to France and

began preparations for the winter with the remaining 78 members of the

expedition, including the explorer and navigator Samuel Champlain. Nearly

half of the men died of illnesses during the first winter and many more

became dangerously ill. Consequently the colony was moved to a more favorable

site at Port-Royal on the Bay of Fundy, in present-day Nova Scotia. There

the settlers cleared and cultivated land and appeared to be making progress.

However, Pierre du Gua's monopoly was revoked in 1607, the colony was

abandoned, and the settlers returned to France. A new attempt to settle

at Port-Royal was launched in 1610, and a rival colony was established

in 1613 in present-day Maine at St. Sauveur on Mount Desert Island. Later

that year, both settlements were destroyed by British colonists from Virginia.

A map showing the major 17th-century settlements and outposts of Acadia

appears below.

The conflict between the British and the French over St. Sauveur and

Port-Royal was merely one of a long series of encounters. As Daigle (1982b:

24) has observed, "Acadia, within the colonial context of North America,

was a border colony. Positioned between the two rival settlements (New

France in the north and New England in the south), the area around the

Bay of Fundy was repeatedly the subject of dispute and the scene of military

engagements."

Port-Royal was occupied by the British throughout the 1620s, but the colony

was returned to France by treaty in 1632. The French established several

small settlements over the next few years, including a number of tiny

outposts along the Gulf of St. Lawrence and in the Lower St. John River

area. By 1650 Acadia had over 400 French inhabitants, including 45-50

families in the Port-Royal and La Héve areas. These families are considered

to be the founders of the Acadian population (Roy 1982: 133).

Port-Royal was occupied by the British throughout the 1620s, but the colony

was returned to France by treaty in 1632. The French established several

small settlements over the next few years, including a number of tiny

outposts along the Gulf of St. Lawrence and in the Lower St. John River

area. By 1650 Acadia had over 400 French inhabitants, including 45-50

families in the Port-Royal and La Héve areas. These families are considered

to be the founders of the Acadian population (Roy 1982: 133).

There has been much speculation as to the possible origins in France

of the founding families of Acadia. Since the publication of Les

parlers français d'Acadie--Enquéte linguistique (Massignon 1962),

most authors have accepted the hypothesis that a great number of families

were drawn from Charles D'Aulnay's estate at La Chaussé near Loudun in

the province of Poitou. D'Aulnay had recruited families for colonization

as lieutenant general of Acadia. While it does seem likely that a sizable

proportion of Acadia's 17th-century immigrants were natives of the western

provinces of Poitou, Aunis, Angoumois, and Saintonge, recent research

also indicates that many came from the northern provinces (D'Entremont

1991: 128-143). They were therefore not a homogeneous group at the outset.

At the time of the first census of Acadia in 1671, the population of

the colony was reported to be 392, and may have been slightly greater

(Roy 1982: 134-135). The number rose by 2,500 by 1714, less than 50 years

later. From the first seat of population at Port-Royal, settlers spread along the shores of the Bay of Fundy and in surrounding

river valleys. Outlying trading posts and Atlantic seaports such as La

Héve remained sparsely inhabited, while settlements around the Bay of

Fundy grew rapidly. This settlement pattern is explained by the fact that

the Acadians concentrated their agricultural activities on tidal flats,

which they diked by adapting techniques brought from Poitou. From 1670

onward, Acadians were attracted in large numbers to the vast expanses

of marshland found in the Minas Basin, and at Beaubassin, at the head

of Shepody Bay (Clark 1968: 139-141).

settlers spread along the shores of the Bay of Fundy and in surrounding

river valleys. Outlying trading posts and Atlantic seaports such as La

Héve remained sparsely inhabited, while settlements around the Bay of

Fundy grew rapidly. This settlement pattern is explained by the fact that

the Acadians concentrated their agricultural activities on tidal flats,

which they diked by adapting techniques brought from Poitou. From 1670

onward, Acadians were attracted in large numbers to the vast expanses

of marshland found in the Minas Basin, and at Beaubassin, at the head

of Shepody Bay (Clark 1968: 139-141).

In 1654 British forces seized Port-Royal and held Acadia for the next

13 years, until France regained the territory by treaty. Port-Royal fell

to the British for the final time in 1710, and Acadia became a permanent

British possession as a result of the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht. As the colony

had no fixed boundaries, the French developed a strategy aimed at giving

up as little territory as possible. They claimed Acadia consisted only

of what is now peninsular Nova Scotia, and they began to erect fortifications

on Ile Royale (Cape Breton Island), Ile Saint-Jean (Prince Edward Island),

and in present-day New Brunswick.

The French settlers who remained in the British territory had learned

to adapt to changing political conditions and had become accustomed to

coexistence with the English. They had adapted their French agrarian lifestyle

to the local environment and had become a people separate from the French

in the mother country.

The French settlers who remained in the British territory had learned

to adapt to changing political conditions and had become accustomed to

coexistence with the English. They had adapted their French agrarian lifestyle

to the local environment and had become a people separate from the French

in the mother country.

The British established a military government at Port-Royal, which they

renamed Annapolis Royal. Rather than putting the Acadians under military

rule, they established a system of representation by delegates, where

any request from British officials at Annapolis Royal was transmitted

to the inhabitants through men chosen by their villages as representatives

(Griffiths 1992: 40-41).

Following the Treaty of Utrecht the Acadians enjoyed a 30-year period

of peace, the longest since the founding of the colony. Due to a very

high birth rate and a low death rate, the population rose to over 10,000

by the late 1740s (Roy 1982: 134). The renewal of hostilities between

the British and French in 1744 marked the end of what has been called

the "golden age" of Acadia. While the war of the Austrian succession was fought both on European and North American fronts,

the Acadians' desire to remain neutral did not keep them out of the conflict.

The war was brought to their doorstep first by the taking of the French

fortress of Louisbourg on Ile Royale by a British force sent by Governor

Shirley of Massachusetts, and then by the 1747 French victory over a Nova

Scotia garrison at Minas, in the heartland of Acadia (Daigle 1982b: 42-43).

Austrian succession was fought both on European and North American fronts,

the Acadians' desire to remain neutral did not keep them out of the conflict.

The war was brought to their doorstep first by the taking of the French

fortress of Louisbourg on Ile Royale by a British force sent by Governor

Shirley of Massachusetts, and then by the 1747 French victory over a Nova

Scotia garrison at Minas, in the heartland of Acadia (Daigle 1982b: 42-43).

Peace was restored by treaty in 1748, but life did not return to normal

for the Acadians. Both the British and French increased their military

presence in the area, the former establishing the fortified town of Halifax,

and the latter founding Forts Beauséjour and Gaspereau in what is now

New Brunswick. The Governor of Massachusetts was infuriated when the fortress

of Louisbourg was restored to the French as the outcome of the peace negotiations.

The rich farmlands of the Bay of Fundy area had long been coveted by the

New Englanders who wished to expand their settlements to the north. The

British colonial administrators in London, wishing to appease the New

Englanders, changed their policy toward Acadians and began to insist upon

the latter signing an unconditional oath of loyalty. Some Acadians responded

by moving from Nova Scotia into territories held by the French, but the

majority remained in their original settlements, maintaining that the

conditional oaths they had signed earlier were still valid. The renewal

of hostilities in 1754 hastened the end of the standoff. What followed

was the tragic deportation that effectively destroyed Acadian society

as it had existed until then.

|

|