|

The

cultural meaning of architectural features cannot be understood apart

from their social and historical context. Accordingly, the salient features

of Maine Acadian dwellings derive from traditional techniques, skills,

and aesthetic values passed down and adapted by successive generations

of crafts people. The builders were not generally professional carpenters,

nor did they work from architectural plans. The construction details of

Maine Acadian houses indicate a high level of woodworking skill. Though

they are generally hidden by exterior Greek Revival or Georgian features,

they help identify the special characteristics of Upper St. John Valley

architecture. The

cultural meaning of architectural features cannot be understood apart

from their social and historical context. Accordingly, the salient features

of Maine Acadian dwellings derive from traditional techniques, skills,

and aesthetic values passed down and adapted by successive generations

of crafts people. The builders were not generally professional carpenters,

nor did they work from architectural plans. The construction details of

Maine Acadian houses indicate a high level of woodworking skill. Though

they are generally hidden by exterior Greek Revival or Georgian features,

they help identify the special characteristics of Upper St. John Valley

architecture.

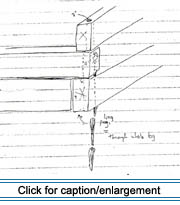

Early

Maine Acadian houses were small, simple, and built of logs. Many were

built piËce sur piËce ‡ tenons en coulisse, a traditional construction

technique featuring horizontal layers of hewn or sawn logs or planks set

"piece on piece." In an Anglo- or Germanic-American log house, the logs

were notched at the corners. In the Valley they were often built en

coulisse. That is, tenons or tongues on each end of the logs (piËces)

or planks (madriers) were inserted into vertical grooves (coulisses)

in upright members at critical locations such as corners and doorways.

One of the virtues of piËce sur piËce construction en coulisse

was that the builder was able to use short logs or planks instead of the

longer lengths needed in other log buildings. It is important to note

that "piËce" is used in the Valley as shorthand term for more than

one type of log construction. Early

Maine Acadian houses were small, simple, and built of logs. Many were

built piËce sur piËce ‡ tenons en coulisse, a traditional construction

technique featuring horizontal layers of hewn or sawn logs or planks set

"piece on piece." In an Anglo- or Germanic-American log house, the logs

were notched at the corners. In the Valley they were often built en

coulisse. That is, tenons or tongues on each end of the logs (piËces)

or planks (madriers) were inserted into vertical grooves (coulisses)

in upright members at critical locations such as corners and doorways.

One of the virtues of piËce sur piËce construction en coulisse

was that the builder was able to use short logs or planks instead of the

longer lengths needed in other log buildings. It is important to note

that "piËce" is used in the Valley as shorthand term for more than

one type of log construction.

The log walls of Valley houses were often chinked with local materials

from the field or forest, such as flax, buckwheat chaff, peatmoss, or

birchbark. This chinking was rather more like marine "caulking" than chinking

of the sort familiar in other regions of the U.S. where logs are laid

up with distinct gaps between them. Since the logs fit flush in piËce

sur piËce construction, "oakum" made of buckwheat chaff or other materials

worked well as chinking.

|

|

|

Brassieur and Marshall (1992) documented three corner-joining techniques

in piËce sur piËce construction of the 19th century: tenons

en coulisse (see above), tÍte de chien or half-dovetailing,

and the "stacked and pegged" treatment found in the Van Buren, Maine,

Maison Heritage (Vital Violette House) and the Roy House at the Acadian

Village in Keegan, Maine. In the latter style, the dressed wall logs were

held in place by trunnels (wooden pegs). The logs were sawn flush at the

corners and alternately stacked one on top of the other. Each corner joint

was secured by two trunnels. While one publication contains a sketch of

this construction method drawn from memory (Bourque 1971: 8ñ9), an extant

example of "stacked and pegged" has apparently never been field documented.

Brassieur and Marshall (1992) documented three corner-joining techniques

in piËce sur piËce construction of the 19th century: tenons

en coulisse (see above), tÍte de chien or half-dovetailing,

and the "stacked and pegged" treatment found in the Van Buren, Maine,

Maison Heritage (Vital Violette House) and the Roy House at the Acadian

Village in Keegan, Maine. In the latter style, the dressed wall logs were

held in place by trunnels (wooden pegs). The logs were sawn flush at the

corners and alternately stacked one on top of the other. Each corner joint

was secured by two trunnels. While one publication contains a sketch of

this construction method drawn from memory (Bourque 1971: 8ñ9), an extant

example of "stacked and pegged" has apparently never been field documented.

Houses were constructed near the St. John River until the middle of the

19th century, when many were moved to sites along the principal road.

For example, three houses examined for Acadian Culture in Maine

were apparently moved from the flats along the river: the Fred Albert,

Val Violette, and Ernest Chasse houses. When houses were moved, they were

often enlarged by adding one or more stories, as in the Val Violette House;

by extending the walls laterally, as may have been the case in the Albert

House; or by expanding both vertically and laterally. The alteration of

these piËce sur piËce ‡ tenons en coulisse houses seems to have

offered little challenge to Maine Acadian carpenters. In those cases of

alteration that Brassieur and Marshall observed (1992), the additions

were accomplished using the same precise axe and adze work and careful

joinery employed in the original construction.

The

typical mid-nineteenth-century Maine Acadian house had an essentially

Georgian plan: two rooms deep, a central hallway, central chimney, one

or one-and-one-half (rarely two) stories high, under a simple gable roof.

The exterior resembled standard large New England houses of the 19th centuryówhite

frame with Greek Revival detailing (cornices and pilasters). Ceilings

were often paneled, and interior molding and finish often echoed the classical

exterior stylistic elements. The

typical mid-nineteenth-century Maine Acadian house had an essentially

Georgian plan: two rooms deep, a central hallway, central chimney, one

or one-and-one-half (rarely two) stories high, under a simple gable roof.

The exterior resembled standard large New England houses of the 19th centuryówhite

frame with Greek Revival detailing (cornices and pilasters). Ceilings

were often paneled, and interior molding and finish often echoed the classical

exterior stylistic elements.

Houses built piËce sur piËce by well-established farmers and merchants

were generally covered on the exterior with planches debout, flush

vertical boards. The planche debout provided insulation and finishing

for a wall, when used with piËce sur piËce bearing-wall construction.

They were sometimes also used on the interior. The vertical boards were

usually tongue-and-groove construction and fitted tightly together. Each

hand-planed or sawn board (planche galbÈe) measured about 2×8

inches. Many houses were finished with clapboards to dress up the buildings

and provide an additional layer of protection and insulation. The roof

frames included massive, relatively wide-spaced, square-hewn, white-pine

rafters. The rafter couples were half-lapped and joined with through-trunnels

at the peak. There was no ridgepole.

There

was a practice of fitting "shipís knees" opposite each other in the loft

or roof area of local houses to provide bracing. Shipís knees are important

technological details that distinguish the construction of Valley houses.

They can be seen in the Fred Albert and Morneault houses. In nautical

usage, shipís knees are vital to a vesselís strength. Shipís knees are

made by bisecting the lower trunk and root system of a tree to yield a

piece of wood with the grain running with the curve for strength. The

application of these substantial braces above the ceiling joists is unusual

in house carpentry and warrants further investigation. Some Valley residents

use the French term coude (elbow) instead of the English "shipís

knee." There

was a practice of fitting "shipís knees" opposite each other in the loft

or roof area of local houses to provide bracing. Shipís knees are important

technological details that distinguish the construction of Valley houses.

They can be seen in the Fred Albert and Morneault houses. In nautical

usage, shipís knees are vital to a vesselís strength. Shipís knees are

made by bisecting the lower trunk and root system of a tree to yield a

piece of wood with the grain running with the curve for strength. The

application of these substantial braces above the ceiling joists is unusual

in house carpentry and warrants further investigation. Some Valley residents

use the French term coude (elbow) instead of the English "shipís

knee."

The construction of Maine Acadian houses changed as the 19th century

progressed. The use of thick pit- or sash-sawn planks (madriers),

set vertically or horizontally, came to replace the use of hewn logs (piËces).

However, documentation of the cedar madriers in the Philias Caron

House in Lavertu Settlement, Maine, indicates that walls built of horizontal

madriers were sometimes joined using the tenons en coulisse

method as late as the turn of the 20th century. A short segment of one

of the madriers, removed during a recent modification of the house,

has a tenon carefully cut into the end that fit into a vertical door frame.

Near the end of the 19th century, balloon-frame houses began to be built

in greater numbers than solid-wall log and plank houses. But the locally

proven Maine Acadian carpentry techniques persisted. Many Valley residents

live in solid-wall houses today. The later-19th-century variants seem

more square and a little taller than the mid-19th-century solid-wall houses.

Many Greek Revival houses were built throughout the Valley from the middle

19th to the early 20th century. A number of houses built in Fort Kent,

Maine, west of the Fish River, have fine scroll-sawn barge boards and

Gothic and Victorian detailing. Some have the appearance of the earlier

Maine Acadian timber-framed houses with gable-ends turned to the street.

The identification of distinctively Maine Acadian architectural features

becomes more difficult with these houses.

|

|