|

The

arrival of Maine Acadians imposed a new order on the land of the Upper

St. John Valley. Initial land ownership in the Valley was granted by the

British Crown. In 1790, Joseph Mazerolle and 49 others received 74 lots,

53 of which were occupied. A second grant was issued to Joseph Soucy and

23 others in 1794 (Craig 1988: 127). The early grants followed a long-lot

pattern: each farm was approximately 1,000 feet wide (60 rods), a mile

and a half long, and perpendicular to the river. The early land grants

by the British produced a linear pattern that is similar to land division

elsewhere in Maine and in French Canada; it provided access to rivers,

lakes, and coastal bays and their associated floodplains and tidal marshes.

The patterns of the Valley may be distinctive in the U.S., however, due

to tiers of lots ranging successively back from the river. Further investigation

is required to discern the distinguishing characteristics of Valley land

division. The

arrival of Maine Acadians imposed a new order on the land of the Upper

St. John Valley. Initial land ownership in the Valley was granted by the

British Crown. In 1790, Joseph Mazerolle and 49 others received 74 lots,

53 of which were occupied. A second grant was issued to Joseph Soucy and

23 others in 1794 (Craig 1988: 127). The early grants followed a long-lot

pattern: each farm was approximately 1,000 feet wide (60 rods), a mile

and a half long, and perpendicular to the river. The early land grants

by the British produced a linear pattern that is similar to land division

elsewhere in Maine and in French Canada; it provided access to rivers,

lakes, and coastal bays and their associated floodplains and tidal marshes.

The patterns of the Valley may be distinctive in the U.S., however, due

to tiers of lots ranging successively back from the river. Further investigation

is required to discern the distinguishing characteristics of Valley land

division.

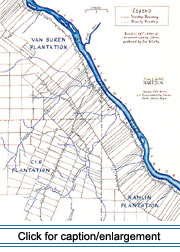

After settlement of lots in the premier rang, the first row of

lots fronting the river, the deuxiÉme rang (second row) lots were

developed. On the north side of the river, settlement continued to at

least six tiers in some places. Because of the curves in the river, these

rangs became oddly juxtaposed, producing an irregular pattern of

land ownership.

On the south side of the river, in what is now Maine, settlement expanded

in this manner in some places until a quatriÉme rang (fourth row)

was established. After the United States acquired jurisdiction over the

south side in 1842, land there ceased to be granted according to the long-lot

pattern. Subsequent land holdings, granted usually to the descendants

of the original settlers or occasionally to new settlers arriving in the

Valley, consisted of a grid system formed by generally square lots of

180 acres each. The square lots represent the American practice of subdividing

square townships. The squares are evident in the Valley today, juxtaposed

with the earlier long, rectangular lots (See map below.)

Under

the terms of the Homestead Act of the State of Maine, homesites could

be secured fairly cheaply, but the new owners were required to settle

duties and perform road labor before land certificates were issued. Each

certificate or grant was called une concession by local French-speakers.

These grants became known as les concessions, and the neighborhoods

associated with them became known as "back settlements." Though the land

parcels in the back settlements are shaped differently from the initial

tiers, neighborhoods continued to develop in the dispersed linear form.

Their orientation may have been toward the shore of one of several large

lakes or toward a road. Like the initial rang communities, the

small back settlements consisted almost entirely of multi-generational,

extended-family groupings. Under

the terms of the Homestead Act of the State of Maine, homesites could

be secured fairly cheaply, but the new owners were required to settle

duties and perform road labor before land certificates were issued. Each

certificate or grant was called une concession by local French-speakers.

These grants became known as les concessions, and the neighborhoods

associated with them became known as "back settlements." Though the land

parcels in the back settlements are shaped differently from the initial

tiers, neighborhoods continued to develop in the dispersed linear form.

Their orientation may have been toward the shore of one of several large

lakes or toward a road. Like the initial rang communities, the

small back settlements consisted almost entirely of multi-generational,

extended-family groupings.

The 19th-century development of les concessions for agriculture

was limited by the fact that the State of Maine had sold most of the remaining

uncleared land during the 1860s and 1870s to large landowners for the

timber (Craig 1988: 132). While the supply of agricultural land shrank,

a flourishing lumber industry developed, providing an economic alternative

to sons who did not inherit land from their parents and who otherwise

would have had to leave the Valley to earn their livelihood.

|

|

|

Nineteenth century farmers in the Upper St. John Valley generally did

not subdivide their land holdings among their children. When parents grew

old, they usually adopted one of two strategies. Many exchanged their

farm, its livestock and equipment, for maintenance in their old age. It

was usually a son who entered into the "deed of maintenance," but some

couples chose unrelated individuals. Other elderly couples sold most of

their land to obtain retirement income. In most cases they sold some land

to their children, but it sometimes happened that all the land was sold

to non-family members (Craig 1991: 221-222).

Lots

initially granted by the Crown were evaluated by the Americans following

the Webster-Ashburton Treaty (1842). The American grants to these lots,

issued by virtue of a provision of treaty, assigned new numbers to the

prior British system and they became known as "treaty lots." Lots

initially granted by the Crown were evaluated by the Americans following

the Webster-Ashburton Treaty (1842). The American grants to these lots,

issued by virtue of a provision of treaty, assigned new numbers to the

prior British system and they became known as "treaty lots."

Similarities do exist between the treaty grants of 1845 and the British

grants of 1790. However, the British numeration of lots began with the

lower numbers downriver and worked up to higher numbers as one headed

upstream. The American numbering system was arranged in an opposite fashion,

with numbers increasing as one headed downstream. It is not always possible

to match lots number-for-number from one system to the other since some

lots in the British system were later divided after the initial grants

were issued and map lines drawn. For example, examination of the succession

of owners of Lot 146, site of the Ernest Chasse House in Madawaska, shows

that the enumeration of treaty lots presents a challenge to researchers.

In this case, determining successive ownership is further complicated

due to errors made in the numbering of this lot and nearby lots.

Nonetheless,

a record of succession of ownership was compiled, from 1846 to the present,

by Dubay (Brassieur 1992) for the Chasse House and seven others. The following

descriptions of three properties include a "river lot" developed in the

initial rang, a "treaty lot" developed after the establishment of the

international boundary, and a lot in les concessions. In addition

to illustrating land tenure, the descriptions serve as an introduction

to land use in the Valley. Nonetheless,

a record of succession of ownership was compiled, from 1846 to the present,

by Dubay (Brassieur 1992) for the Chasse House and seven others. The following

descriptions of three properties include a "river lot" developed in the

initial rang, a "treaty lot" developed after the establishment of the

international boundary, and a lot in les concessions. In addition

to illustrating land tenure, the descriptions serve as an introduction

to land use in the Valley.

|

|